On Wednesday morning, pressed and dressed as neatly as possible, Madame Vastra and Jenny entered the front gate of the Bank of England. Jenny thought she’d done a fair job at finding a proper hat and netting that was a close match to Vastra’s cloak and then sorting out how to get it to stay on Vastra’s head without benefit of hairpins or hatpins.

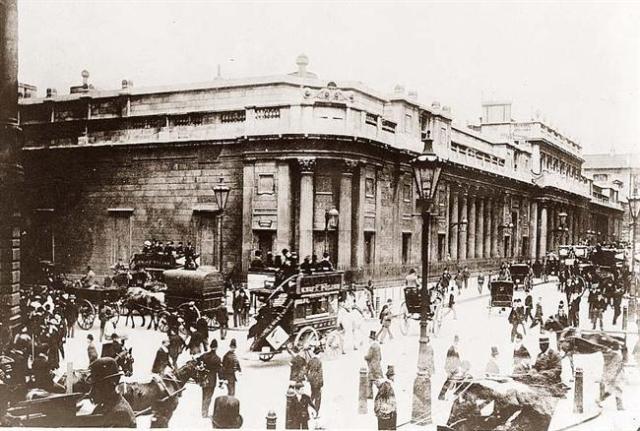

An elderly, red-coated porter greeted them, and directed them to Mr Thackeray. They crossed a small court-yard, mounted a few steps and found themselves in a large hall: at least a hundred bank-clerks and customers were there. Men, women, and boys were present, some walking arm in arm as if they were in a park. Jenny spotted Mr Thackeray (Vastra was still mystified at how easily Jenny could tell Apes apart,) and guided Vastra over to him.

“Hello, Mr Thackeray,” Jenny greeted him, “Madame Vastra and me are glad to see you looking better.” Jenny saw the man give a small sigh of relief; she’d answered the riddle of how to address Vastra. He greeted them happily, obviously proud of his bank, and eager to show it off to his new friends.

Mr Thackeray led them around the room, and they watched people exchanging money, giving it to the clerks, and the clerks fetching it from or delivering it to a nearby vault. It was as if all these people had stepped into a neighbourhood shop specializing in money. In long rows along the walls, the bank clerks sat writing, adding up accounts, weighing gold, and paying it away over the counter. In front of each was a bar of dark mahogany, a little table, a pair of scales, and a line of people waiting for their turn. The business flowed smoothly, and no one was kept waiting for any length of time. Mr Thackeray took a moment to show Vastra and Jenny the books the clerks were writing in, which he called ‘Day Books’ and to point out the small books the customers carried, which he called ‘pass books’ as they were ‘passed’ between the clerks and the customers to be updated. Each passbook contained a record of the client’s transactions with the bank. Mr Thackeray explained that each afternoon, when the bank closed, the day books would be read out, and the transactions entered into the Bank’s official ledgers; great bound books that recorded all the clients, and all the transactions for every client.

“I’ve secured special permission from one of the Bank’s directors, Mr Dawes,” continued Mr Thackeray. “I’d like to show you some areas that most people never see. I hope you will find them interesting.” He led Vastra and Jenny down a set of winding stairs, to a large door. He knocked, and then led them inside to where a balding older man in a dress coat sat behind a small desk.

“This gentleman is the librarian of the Bank,” said Mr Thackeray.

The man in the black dress-coat opened a door in the railing, and bade them enter. He showed them an enormous number of parcels and bundles of notes, ranged along the walls up to the very ceiling. He explained that the library of the Bank was a room that stored notes that had been paid in at the Bank. They were valueless; the Bank never issued the same note twice. They were kept and locked up in the library, for many years, in order to be produced in the case of a theft or forgery. Afterwards a set number of years they were burnt. Most of the notes were payable “to the bearer” and included a number. Jenny asked what a bearer was, and Mr. Thackeray explained it was the person who bore, or possessed, the note. The banks would record who was issued the note, or who had deposited it, but the notes could be freely given and used by anyone. He showed Jenny and Madame Vastra some specimens worth five and ten pounds each. They were simple pieces, printed on one side only.

Every now and then clerks came in with fresh bundles of the notes. A few minutes ago these papers were worth who knows how much money. “They are now mere waste paper,” explained Mr Thackeray. “Many notes lead long and honourable lives; they go to the Continent, to India, or Port Adelaide; and return to the Bank much the worse for wear after all their journeys. Other notes have scarcely a day in the world; to-day they are issued, and to-morrow they are paid in for deposit or exchanged for gold.”

Next Vastra and Jenny followed Mr Thackeray into the guard-room, where a detachment of soldiers from the Tower passed every the night, to protect the Bank “in case of an emergency.”

They then went to the Bullion Office, a subterranean vault, where the Bank kept gold and silver bars from Australia, California, Russia, Peru, and Mexico; here they weighed them, purchased them, and then the Bank sent them to the Mint, just east of the Tower of London, to be re-coined. Jenny asked if any of the bank staff had ever been accidentally locked in the vault at night, as it looked as if someone could get lost in here very easily. Mr Thackeray said it had only happened once that he knew of. Vastra gave the inside of the doors a knowing glance; they were primitive, and seemed designed to keep people out more than keep them in. “Did the man unlock the vault door, and relock it behind him?” she asked.

Mr Thackeray blinked, startled. “Well, yes, actually. However, it still took him a fair amount of time to get the door unlocked.” Vastra simply nodded, and filed the information away.

Mr Thackeray then led them through several passages and knocked at a large door, which opened from the inside. Two gentlemen, in black dress coats and white cravats, stood in a large room. The walls were covered with iron lock-ups and safes. This, he explained, was the Treasury of the Bank, where they keep the new notes and coins. Mr Thackeray picked up a small gold coin, and showed it to Jenny. “You know what this is, right?”

“It’s a sovereign, sir” said Jenny, on her best behaviour. “It’s worth one pound sterling.” ‘Just over 3 week’s wages for me,’ she thought.

Mr Thackeray nodded, clearly pleased, and then passed a slip of paper to one of the gentlemen. The man looked at Mr Thackeray’s order, and, with gentle dignity, he turned and opened one of the iron safes. It was filled with bags. He took two of them and put them into Jenny and Vastra’s hands, and explained that the bags contained 500 or 1000 sovereigns each. Jenny stared at the one in her hands, and murmured, “Five hundred pounds! I’ll never see that again in my entire life!”

Mr Thackeray looked at her, and said, “Miss Jenny, you must not think like that. You’re a brave and bright young girl. If you apply yourself, I believe you can someday see five hundred pounds again.”

And at that moment, Vastra decided that Jenny would, at least, have the opportunity to supervise a household where five hundred pounds was a commonplace sum. She had no idea how to go about it, or if Jenny would even be interested in doing so, but the girl was still young, so she had time to plan something out.

“Or perhaps you’ll marry well!” continued Mr. Thackeray. Jenny managed not to roll her eyes. What sort of rich toff would ever marry a cockney maid? It only happened in stories.

The other gentleman then took a bunch of keys, and opened a large closet filled with notes. The most valuable and smallest bundle was put into Jenny’s hands. “You have there,” said he, “two thousand notes of one thousand pounds each.”

Jenny frowned a moment, doing sums in her head. “Two million pounds sterling!” She exclaimed. Vastra agreed, surely it was an enormous sum to hold in one’s hand. She wasn’t sure she could ever match that. Both of them missed Mr Thackeray’s look of surprise at Jenny’s speed at doing the sum. He knew it was a simple calculation, just counting the zeroes, but still… Jenny took a deep breath, and returned the notes to their keeper, almost glad to be beyond temptation. They left the Treasury, without being any richer. Of course, they were not allowed to carry off its contents. But both Vastra and Jenny certainly had food for thought.

Finally they entered another large room, with a neat, pretty steam-engine in it, and with a variety of other small machines whose complicated wheels were kept in motion by the engine. The largest object in the room was a large table, literally covered with mountains of sovereigns. A few officials, with shovels in their hands, were stirring the immense glittering mass.

“Here they weigh the sovereigns,” whispered Mr Thackeray. Besides a mysterious system of wheels within wheels, each of machines had an open square box, and in this box, two segments of cylinders, with the open part turned upwards. A roll of sovereigns was placed into one of these tubes, and it passed slowly down, one gold piece after the other dropping into a large box on the floor.

The clerks filled the tubes. The sovereigns slid down, but just at the lower end of the tube, whenever a sovereign of less than full weight touched that point, a small brass plate pushed the defaulter into the left-hand compartment of the box, while all the good pieces went to the right.

One of the clerks explained, “The Bank selects the full weighted sovereigns from the light ones, because all the money we pay out must have its full weight.”

“And what do you do with the light ones?” Vastra asked.

“We send them to the Mint after we’ve marked them. Shall I show you how we do it?”

He took a handful of the condemned coins, and put them into a box, which looked like a small barrel-organ. He turned a screw and there was a rushing noise in the interior of the box, and all the sovereigns fall out from a slit at the bottom. But they were cut through in the middle. The Victorias, and Williams, and Georges, all cut through their necks, in fact, beheaded!

Mr Thackeray smiled slightly, “That’s what the we call ‘marking a bad sovereign.'”

Their last stop at the bank was the office of Mr Dawes, the director who had authorized their tour. The thin, white haired man looked up when they entered, sat back with steepled fingers and regarded them shrewdly, if politely.

“So you’re the woman who saved my manager, and the young gel who saved the ledgers in his care, eh? It was quite a surprise when Thackeray told me of his rescue. Especially since none of the men in the street were brave enough to help.”

The pair glanced at each other, and to Mr Dawes surprise, it was the young girl who replied:

“Well, Madame Vastra helped me out of a fix a few weeks ago, Sir. Thought I’d pass on the favour. Couldn’t let the gentleman be strangled in front of me without doing something, now could I?”

“And since Jenny was wise enough to call out before she dove into the situation, I thought it best to help before she managed to get herself killed,” added Madame Vastra. Dawes caught the slight head-cock as the woman turned to regard the girl despite the veil she wore, and from that and her tone of voice, he could well imagine a look of fond exasperation bestowed on the youngster. Interesting pair, he thought. The girl was pure cockney, probably a poor labourer’s child or orphan if she was so ready to fight, while the woman had a cultured voice with a slight accent. Unlikely that they were simply neighbours or friends; Employer and employee? Probably mistress and maid most likely, he decided, as the child used the woman’s title. He judged the girl to be twelve or thirteen, a sensible age to begin in service as a scullery or laundry maid.

“And the two of you managed to beat a pair of London street toughs,” observed Dawes.

“They were not very competent, and we caught them by surprise…” said Madame Vastra. ‘And I have years of experience as warrior and hunter and Jenny’s proving to be a very quick study in the art of self-defence,’ she added to herself.

“Sir, what was in those books that the toughs wanted?” Jenny asked.

Mr Dawes eyed her for a long moment. It was both a reasonable and impertinent question. But since the pair had risked their safety for Thackeray, he owed them a civil answer: “The Manager at Sherwin and Somes Bank asked me to look over these ledgers and daybooks.” He waved at the stack on his desk. “There are some entries that he felt would benefit from being reviewed by an experienced eye.” There were, in fact, some entries that were damned disturbing. No point in troubling the ladies with that information though. “They may simply have wanted information on which clients to rob.” Or they might have been paid to snatch the books. From what he had seen, Dawes could well believe that explanation as well.

Mr Dawes regarded the pair gravely for a long moment. “I will ask though that if you see either of those toughs near where you work or live, you send a message to Thackeray or me immediately. I’m worried that you may have drawn the attention of some true scoundrels, and I don’t want to see you hurt as a result of your bravery.”

When both the ladies nodded, he relaxed a bit. Some of these modern women would take offence at being protected, but these two clearly knew their limitations. Luck had been with them when they’d rescued Thackeray, but luck such as that could not hold for long.

Mr Dawes glanced over their clothes, and saw far more than most women would be comfortable with. The pair before him were, if not flat broke, then certainly not very well off. Their clothes, though clean and pressed, were worn and patched, and Madame Vastra had an odd combination of hat and cloak and dress. He had no idea how she could see through the thick layers of veil; he couldn’t see a hint of the woman’s face. But they’d obviously tried, and Dawes didn’t mention the slight trace of boot blacking he could see on young Jenny’s hand. They’d asked for no financial remuneration, though Thackeray had mentioned he was going to buy them lunch. Dawes was wealthy in his own right, but he was the third son himself of an improverished country squire, and understood that life sometimes depended on the friends one made. So it was time, as the girl Jenny had said, to ‘pass on the favour.’

“Miss Jenny, this is for you, for raising the alarm, bringing Madame Vastra to the fight, and being brave and pitching in yourself,” said Dawes, taking her hand and closing it around a gold sovereign. “Don’t spend it if you can help it. Keep it safe. Someday it may help you, as you helped Mr Thackeray.”

“Thank you both again. Good luck to you, and may we meet again.”

As promised, Mr Thackeray took them to lunch. Earlier, Jenny was able to suggest that Madame Vastra would love some nice rare roast beef, (she thought ‘raw’ might be a bit much to ask for) and Mr Thackeray knew a perfect spot nearby. He sent a bank messenger to arrange things and the three of them were soon seated in ‘Old Edwards’, in a snug little room away from the noise and cigar smoke in the main restaurant. Jenny had a nice meal, although she had to keep watching Mr Thackeray to see how he held his fork. Her knife, of course, Jenny had no trouble with. Even Madame Vastra enjoyed the meal, as the roast beef was very good, even if it was cooked, and the accompanying peas and mashed potatoes, while very different from what she was used to, she could at least eat in small amounts.

While Madame Vastra did not remove her veil to eat, Jenny had fun distracting Mr Thackeray at the critical moment, just as Vastra moved her veil slightly aside for each bite. It took the man a bit longer than it should have to catch on to the game, but Vastra decided to be charitable and assume the man was humouring Jenny. Eventually he simply acquiesced to the unspoken request to respect Vastra’s privacy, and the three of them enjoyed a very pleasant lunch.

After the meal, they bid Mr Thackeray a polite goodbye. Vastra, still very at sea over Ape courtesy, simply started to turn to leave, but Jenny caught Vastra’s arm to stop her, and then said “Thank-you” properly for both of them.

“Are we going to send a note if we see the bully-boys again?” asked Jenny as they walked back to the flat. “Didn’t want to upset the old gent by saying no.”

“Yes, I think that would be wise,” said Vastra. “Not for our protection, but because there seems to be a mystery here, and I’d like to know what is going on. That is a reasonable way to stay in touch.”

“Know you can keep us out of trouble, ma’am. I’m more worried about who’s protecting Mr Thackeray!”

A hum of agreement was Vastra’s only reply. Jenny glanced over and saw the woman was deep in thought.

Vastra had found out about Banks. And that’s when the trouble started…

That evening, after she cleared away the supper dishes, Jenny took the stairs to the roof for her daily training. Madame Vastra was already there, pacing, grumbling and swearing when Jenny arrived from.

“Not late, am I?” Jenny asked, seeing Vastra in a high temper and a foul mood. ‘She’s on a right tear tonight,’ thought Jenny, ‘better talk it out with her before she decides to take it out on me.’

Not that Vastra had ever hit her, except during training, and even that was usually by accident. For that matter, after the first day of training, Vastra hadn’t lost her temper with Jenny, and Jenny had taken care not to give her a reason to do so. It was a strange little truce that they’d worked out. Vastra’d not been so angry recently, and Jenny had hoped that the quiet would last longer. No such luck, though.

“No, no, you’re fine,” growled Vastra. “I was just thinking about that bank! It is absolutely infuriating that all that money is just sitting around, not being useful, while you work so hard for less than one of those little gold coins! I am determined: between the two of us we can do better than 6 shillings a week! Who has all that money, anyway? Where does it come from?”

Jenny shrugged. “The Crown and the Government get it from taxes. The gentry inherited it. Companies like the railways and the East India Company, the merchants and landlords charge what they like, and people either pay it or go without. As the saying goes: them that has the gold, makes the rules.”

“Knowing the lack of morals of Apes, many of those are probably as corrupt and criminal as the Scorpions,” growled Vastra. Jenny wanted to protest, but decided to let Vastra rant instead. Safer for her that way.

Vastra paced back and forth some more, grumbling, but then saw Jenny staring off into space and frowning. “What is it?” snapped Vastra.

“Well, I was just thinking,” said Jenny. ” ‘Member I told you that the Scorpions have their fingers in a lot of crimes? People say they make a good bit of coin from that. But when we saw the Scorpions with my Da, they were dressed as poor as the costermongers and dock workers. It didn’t look like they had much money. So if the stories are true, why are they so poor?”

“You’re wondering what becomes of the money?”

“Well, unless the stories are wrong.”

“Stories to keep the locals living in fear? That’s possible.” Vastra turned the idea over in her mind. She was learning to listen to Jenny; the hatchling was young, but she paid attention and asked good questions, even if she didn’t know the answers.

Vastra shook her head after a moment. “This are interesting, but it’s a distraction. Meanwhile, we have training to do. Plot and plan later.

“Time to start. Focus on the Now, and we’ll begin.” They exchanged the salute with weapons that Vastra had taught Jenny, and they commenced the lesson.

After giving the situation some deliberation, a day later Vastra announced a new plan to Jenny.

“I will spend some time finding Scorpions, following them, and learning their nests and habits,” said Vastra. “I want to follow up on your thought about where the money they swindle is going. I’ll also gain a better idea of how they are organized.”

“Brilliant, ma’am. Let me get my things…

“No Jenny.” Vastra held out a hand. “You are not coming with me.”

“But ma’am, I know the streets…”

“You can’t come with me,” Vastra said firmly. “Not this time. If you are caught by the Scorpions… Do you understand how much danger you are in?” Her voice turned fierce, “If I had prey such as you, I would never give up!”

Jenny stilled, caught by surprised.

Vastra continued, “We defeated them. Remember what your friend Ro… Tom, said? They were grown, dangerous Apes embarrassed by a fighting female hatchling and a demon with a sword. They need to find you to prove it’s not true, and to keep their pride.”

Jenny rather liked Vastra’s causal use of “We defeated them.” Made them both sound dangerous. As far as Jenny was concerned, Vastra had thoroughly trounced the men and Jenny had merely punched and yelled.

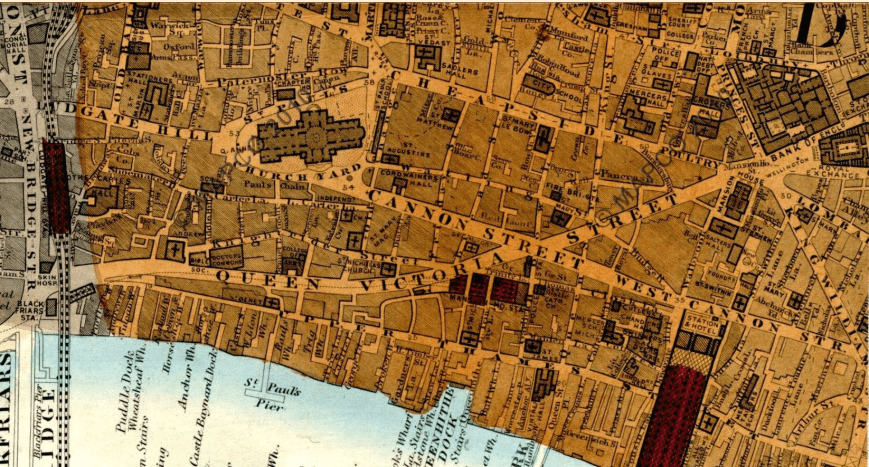

Vastra watched Jenny. Her pet looked slightly mollified, as if she was considering the words a little. Vastra felt a trickle of pride, remembering the little monkey who refused to cower or give in to her attackers. She could see Jenny thinking it through, and Vastra continued, “For now, promise me that you will not venture east of Bishops Gate and Grace Church Street.” That was a line less than a mile east of them, just past the Bank of England, running roughly North-South. Another mile beyond that, close to the Thames River, was Jenny’s old home.

Jenny saw an objection, “But ma’am, the markets are east of there.” Not that she was able to go to them often, but the food there was fairly cheap. She could stretch a shilling to cover a decent amount of food, especially if it was blemished or getting old. A potato with some small eyes was still a decent potato. And perhaps a bit of meat other than pigeon might be smart.

The other day Vastra had put aside one of the birds she’d captured and told Jenny not to eat it. It turned out that Vastra had accidentally poisoned it when she caught it with her tongue. Jenny had been torn between disbelief and resignation that Vastra was quite capable of killing something with poisonous venom. It seemed to her the surprises about Madame Vastra just kept coming.

“Then I will accompany you when you need to shop,” Madame Vastra continued. “But even with me, for now, don’t venture east of the Coal Exchange and Billingsgate Market. Jenny, I am only trying to keep you from danger.”

Jenny sighed; she didn’t want to miss the excitement, but Madame Vastra was doing her a favour. She must not grouse about being left out. “All right. Ma’am. I’ll stay put.”

Vastra donned up her cloak over her cutlass, and pulled her hood into place. “I’ll see you in a few hours.”

Vastra made her way to Beer Lane. While she might not know where to find the Scorpions nests, she knew at least one contact point for them: Jenny’s father. She waited patiently in the shadows of a building across from Jenny’s family flat. Eventually she saw Jenny’s father come out and followed him east towards the Basins and the docks. At one point, she saw several labourers who had features similar to the Scorpions, ‘Chinese’ Jenny had said, from a distant country, but they ignored the man she was following and she decided they were most likely simply fellow workers in the area. Finally, Jenny’s father was confronted by two ‘Chinese’ men, and they exchanged words. Vastra wasn’t able to hear the exchange, but when the Apes parted, she kept in the shadows and followed the newcomers.

It took Vastra several days to locate the various Scorpions operations. Each time she returned to the flat, she relayed her findings to Jenny, who started keeping notes in her copybook, in order to keep track of what Vastra had seen. Vastra approved, and gave Jenny money to buy a better notebook and a proper pen and ink, so she could keep the notes organized. It was good practice in writing and thinking for the hatchling. It also kept her interested and involved in the situation without endangering her.

In turn, Jenny was surprised how quickly Madame Vastra could work. Madame enjoyed the chance to hunt again, didn’t tire of the chase, and her hunting instincts and experience worked well to London. She understood how to use shadows, and alleyways and wasn’t put off by some of the rougher characters found in both. Usually she was able to either ignore them or frighten them off. On two occasions, stronger measures were needed.

Vastra took the time while returning home to order her thoughts properly and then spoke slowly and clearly so that Jenny, who still needed a great deal of practice, was able to keep up with her while writing. In relating her findings to Jenny, Vastra left out both the ‘midnight snacks’ she’d indulged in.

Slowly a picture began to emerge of an intricate web of activities that fed funds from the people of London who could least afford to lose it, the poorest of the poor; through a series of Tong ‘trusteds’ as Vastra called them, and finally up to the top tier. Vastra was surprised to find that three of the four Apes in that top tier didn’t look like the ‘Chinese’ at the bottom, and longed to bring Jenny with her just once to confirm her suspicions that the ‘Chinese’ were almost as much victims as their supposed prey.

The problem was that the closer to the top tier that Vastra approached, the more secrecy and security surrounded the Apes. The areas of the city in which they lived and worked were definitely not poor or what Jenny called ‘common folk.’ Vastra, cloaked as she was even as the days were warming up, did not fit in as well, except after dark. She found she needed to go out later and later at night. And she returned later as well, so that Jenny was sometimes half-asleep when she finished her notes.

One morning, Jenny was re-reading what she’d written the last few days. When she sorted out that Vastra was now ‘hunting’ in the more prosperous West End, Jenny almost started bouncing with excitement.

“I can help you now! Nobody in the West End would even glance at me! Give me a day; I’ll go to the rag pickers and find a disguise!”

“You won’t know what to look for. These Apes…”

“Take me with you tonight and tomorrow. Show me what you’re looking for, who you’re following. Then let me watch by day, and you hunt at night.”

Vastra made a little hissing noise that meant she was unhappy. “I’m supposed to be protecting you.”

“You are. But I’m as safe as houses in the West End. The little Scorpions won’t go there, and the big ones don’t care about the likes of me. ” Jenny could see that Vastra was not ready to give in.

“Make you a deal: I’ll see what I can find during the day. You can check it in the evening. If I can’t do it, we’ll stop, and you can hunt alone again. I’ll need to keep up the cleaning job here anyway; still need the money if I want to eat more than pigeon.”

Vastra just shook her head. Jenny was up to mischief again, but perhaps she could make it work.

Madame Vastra had to concede, when Jenny decided something, it was done with all the speed her young pet could muster.

Later that morning Jenny took two shillings from the money Vastra was holding for her, and went to find a disguise. She returned with some bits of white cloth.

“I got a cap and apron from the rag picker.” She put the apron on over her dark dress.

Then she did something that surprised Vastra; she took her hair ‘tail’ (it was the only term Vastra could think of,) twisted it around, and stuck some bits of metal in it. It stayed at the back of her head, and Jenny placed the white cap over it, and fixed it with more metal bits. Then she picked up a worn little basket that she’d bought to complete her outfit, and examined the result in a bit of mirror out in the landing of the stairway. “This’ll do nicely,” she said. “Only other servants will ever notice me, and they’ll think I’m just a scullery maid on an errand.”

Vastra had seen some of the hatchlings dressed like this, but had never given them much thought. She admitted to herself that Jenny might be right. She looked very different.

Jenny put away her disguise for the evening, and in her plain clothes went with Madame Vastra on her hunt. She’d rarely been this far west in the city in the city before, and seemed eager to check all the street signs and try to get her bearings. The weather was clear, which helped them, and they spotted almost all their quarry over the next two evenings

Jenny confirmed Vastra’s suspicion that several of the senior Scorpions were not Chinese. She was not able to see the last man; he tended to stay in the East End near Limehouse where Vastra had first seen him. Vastra was still sticking to her rule and not letting Jenny go into Scorpion Territory.

Thursday morning Jenny dressed in her scullery maid clothes, took her basket, and headed out. Vastra quietly followed her as long as she could, but when the streets grew busier and busier she could see people staring at her more and more, so she returned to the flat to wait. She spent the time re-reading Jenny’s notes, and convincing herself that she was merely concerned about the success of the scheme, and not overly worried about her pet’s safety. Late in the afternoon, Jenny returned, tired but happy. She was carrying what looked at first glance like bits of dirt in her basket.

“Picked up some potatoes and spring onions, so it’d look like I was on an errand for the kitchen. Blimey, food’s expensive there! Be good for pigeon stew though.”

Jenny showed Vastra the basket. Inside where a few round dirty brown lumps, and two long green things with a white bulbous end and tiny tendrils. Vastra was aghast, how could Jenny eat these repulsive things? The girl must have a strong stomach.

Jenny pulled out a slip of paper written in pencil. “I got two of their addresses.”

“Do you have names for them?”

“Have one. Heard his butler say it at the door when he went in. Don’t have the others yet.”

“Still, that’s an excellent start. You have a talent for this.”

“Got real lucky too. The other must have thought it was too nice a day for a carriage. He went for a nice long stroll. Right to a bank.”

“Which bank? Did you see the name?”

“Yes, Madame.” Jenny looked back at her slip of paper. “He went to Sherwin and Somes Bank on Paternoster Row.”

“The Ledgers that Mr Thackeray was taking to Mr Dawes when he was attacked. The ones that Mr Dawes was reviewing… They were from that bank. Correct?”

Jenny looked up with a grin. “Thought the name was familiar. Yes, that’s the one.”

Vastra nodded, pleased. “Well done, Jenny. Very well done.”

Slowly, they built up observations and notes. By the end of April, Vastra was able to put together a fairly detailed picture of the senior ‘investors’ in the Scorpions, their highest officers, and which banks they dealt with. A bank on Aldridge Lane, another on High Holburn and Sherwin and Somes on Paternoster Row were the preferred institutions.

They had names and addresses for some fourteen men, which banks each dealt with, and including a little on the senior Chinese Scorpion. Vastra had never seen him near enter a bank, so where he stored his funds were still a mystery.

Still what they had was enough for Madame Vastra to develop a plan of attack against the Black Scorpion Tong.

Since the Bank of England was less than ten minutes away, and Mr Thackeray liked the place, especially the house bitter; he started to visit the Gin Palace occasionally. Usually he came early in the week, before the more boisterous crowd arrived. He’d bring other bank workers sometimes as well. It helped that he also liked Jenny and Madame Vastra, though they were never in the Gin Palace itself in the evenings. From time to time he could find them if he poked his head out the back door, sitting in the Area at the back and enjoying the twilight. Usually Madame Vastra would speak with him for a bit if he kept to the commonplace, or about news around the city. Any personal questions, he found, were politely but firmly turned aside.

Jenny would often sit near them, either on the bench with Madame Vastra, or on the nearby stairs, or sometimes on the ground. One evening, Thackeray noticed that she seemed rather sleepy, and as she sat on the ground near Madame Vastra, she kept nodding off, fighting not to slump against Vastra’s legs. James was amused to see the young girl lose the fight, sliding gently against the bench at her back and the skirts of her employer. Madame Vastra glanced down, and shook her head.

“She’s been very busy these last few weeks, running errands for me. It’s tiring her out, but she’s young and she always bounces back.”

“What sort of errands, Madame?”

Vastra considered him for a moment. This might be a good time to start laying a foundation for some changes she wanted if her plans came to pass.

“While I was born not far from here, I’ve lived outside London and the British Empire since my childhood. I’ve only recently returned. My assets, both cash and notes, were unexpectedly delayed in arriving, which is why I am living at this place. Jenny has been assisting me to become familiar with the City, and to learn the about the A.. people here. In return she has a place to sleep and food to eat, and I am educating her.”

“As well, for my own reasons, I am not… comfortable going out during the day. Jenny helps with that as well, both getting me out of my flat, and going out and about on my behalf.”

“You mentioned your funds… Is there any help I can give you there? The Bank has both national and international connections, of course.”

“You are very kind to ask. The matter only requires some patience to resolve, I believe. You are aware of the recent troubles in Russia?” Vastra herself had only the vaguest idea, she was only aware that someone important had died. But she wanted Thackeray to believe that while she was currently in strained circumstances, she shortly expected to be in an improved situation.

“The assassination of the Tsar?”

Vastra made a note to find out if Jenny could explain what a Tsar was. “Among other things,” she hedged.

Thackeray nodded again, “Yes, we’ve heard about the unrest. The newspapers have been full of reports.”

Vastra added to her mental notes to also get some newspapers and do some research.

“I’m not sure how much I should tell you…” and that was the truth. She’d wanted to lay some groundwork for the future, but she hadn’t thought it out. Mr Thackeray was very bright in his own area of expertise. She’d underestimate the Ape.

At that point, Jenny shook herself awake. She glanced up at Madame Vastra and then at Mr. Thackeray, blinking owlishly. “Sorry ’bout that,” she muttered. “I should go up. Must be more tired than I thought.” Jenny levered herself up, slightly unsteady, stretch and yawned, remembering half-way through to cover her mouth. She grinned sheepishly at Thackeray. “Sorry, sir. Good night.” She glanced back at Vastra, who rose as well.

“I will come up as well. Mr Thackeray, it has been a pleasant evening.”

“Madame, it has been most enlightening. Please remember that if there is anything the Bank or I can do to assist you, we are at your disposal. And please, call me James.”

Behind Mr Thackeray, at the door to the stairs, Vastra could see that Jenny was suddenly shaking her head and mouthing “No.” Her pet was warning her off from using the Ape’s name, and for now she’d heed the warning. She decided on a neutral reply.

“I will remember. Good Night.”

And with that, she turned and left with Jenny.

“Sorry to bust up your evening, ma’am, but it sounded like you needed a rescue.”

Vastra’s pride was stung. “I had the situation under control.”

Jenny shook her head. “If you say so, I’ll take your word for it.” But it didn’t sound like that to me, she thought.

Vastra fumed for few moments, and then quietly asked, “Do you know what a Tsar is?”

Jenny shook her head, amused. “Nope. Want me to buy a newspaper or two tomorrow?”

Vastra sighed, “Yes, that would be wise. I thought you were asleep.”

“Just dozed off for a moment. Heard most of what you said about not living here for years. How true is that?”

“All of it. I was born near here. Until recently, I did not live in the City of London or the British Empire.”

They separated at the door to the flat, Jenny to the Necessary down the hall, Vastra into the room to begin the process of getting her layers of clothing off for bed. When Jenny returned, she helped Vastra as needed.

“What were you warning me about when Mr Thackeray asked me to call him ‘James’?”

“Wasn’t sure if you understood what that means. He’s sweet on you, Ma’am.”

Vastra frowned. “`Sweet’ on me?”

Jenny grinned. “He likes you. Wants to get to know you better. Might be thinking of courting you.”

Vastra cocked in head in confusion. “Courting me?”

Jenny nodded, “He probably thinks that you might like some better company than a girl like me. So he’ll ask you out, spend some time with you, get to know you. Maybe at some point he’ll ask you to marry him.”

Vastra thought over what Jenny had told her about being married. It was a way for two people to live together, share a household, and perhaps start a family and have hatchlings.

Vastra was appalled, “Are you saying that he wants to MATE with me?”

Jenny’s jaw dropped open. Even for Madame Vastra, that was pretty blunt. She took a moment to collect herself. “Well, eventually… maybe… yes? Pretty sure that’s a while off yet. He’s barely met you. And he’s never even seen..”

“He’s an APE! A male APE! Gods, that’s disgusting! Me… no, ANY of my people, mating with an APE?”

Jenny recoiled, surprised at Vastra’s obvious revulsion. “He doesn’t know you’re not a regular person, now does he?”

“It doesn’t matter. How could he even think…!”

“Oi!” Jenny caught Vastra’s attention. “He’s just trying to be nice, ma’am. He seems a decent sort, with a good living, and polite manners. He’s not a dockworker offering you a trip over a barrel! Calm down. I’ll warn him off, as I take it you’re not interested.”

Vastra shivered. “No! I would never let an Ape that close to me!”

“But…”

“Enough! I don’t want to discuss this anymore. I’ll probably have nightmares as it is. Get in bed and go to sleep.” She waved her hand at the bed, distracted. Jenny slid in next to the wall, and stretched out with her back to Vastra, who slipped in beside her, facing the room, their backs close but not touching in the narrow bed. They’d settled into this routine weeks ago, and neither gave it any thought now.

It was on the tip of Jenny’s tongue to remind Vastra that Jenny herself was a so-called ‘ape’ but she held her peace. She was too tired to argue, and besides, she really didn’t want to get kicked out of the soft bed to sleep on the floor tonight.

The next afternoon, after Jenny returned from her errands, complete with ‘The Times’ and ‘The Guardian’ she decided to ask about the other part of the last night’s conversation that had interested her: Vastra’s mention of expecting funds. She’d needed to give that some thought; she was pretty sure Vastra had some money hidden in the room. Vastra had a little bag with Jenny’s earnings in it from which she gave Jenny food money when she needed it, but the bag never seemed to get smaller after the rent was due. Which Jenny guessed meant that Vastra was paying the rent with other savings. But yesterday had been the first time Madame had mentioned having more money somewhere.

While Vastra read the papers, Jenny worked on her notes. After a while, she worked up the courage to ask, “Madame, what does Russia have to do with your funds being delayed?”

“Ah, you heard that bit as well, did you?” Vastra leaned back in the chair, and regarded Jenny for a long moment as the hatchling finished her writing and closed her notebook. “Have you ever heard of ‘undermining’ a stronghold?” she asked.

Jenny shook her head, confused by the change in subject. “I know mining is digging up coal and gold and things, and I think that a stronghold might be like the Tower of London near Da’s flat, but I’ve never heard of digging coal under the Tower. What’s that got to do with Russia?”

Vastra tried not to smile at Jenny’s sensible but tangled attempt to reason out the question.

“Nothing. The part about Russia was a distraction, to help explain why we will suddenly have a great deal of money. By the way, according to these newspapers, the Tsar was the Russian King. He was murdered in mid-March by revolutionaries.” Jenny nodded. Interesting and no doubt his family was sad, but otherwise not particularly important. What was this about ‘a great deal of money?’

“To answer the original question: ‘Mining’ or ‘undermining’ a stronghold,” explained Vastra, “is a siege tactic, when the enemy has a strongly defended fortified position. A frontal attack, not matter how strong, would be suicide. But undermining involves digging under the foundations of an enemy fortress or stronghold and collapsing a section. Typically once part of the wall of the stronghold collapses, warriors are sent in to overwhelm the enemy forces. It was far out of date in my time, but our warriors still learned the theory, as it sometimes applies in other ways.”

“That’s what we’re going to do. We’re going to take down the Black Scorpions by undermining their strongholds, which in their case is the money they’ve made. In other words, we’re going to attack their finances.”

Jenny shook her head again, baffled.

Vastra smiled and explained, “That’s where our funds are going to come from. We’re going to steal their money. Or to put it in the words of your hero Robin Hood: We’re going to rob from the rich and keep it for the poor.”

“I don’t think it’s supposed to work like that,” muttered Jenny.

Authors Notes for Chapter Two:

The description of Vastra and Jenny’s visit to the Bank of England is heavily based on “Max Schlesinger, Saunterings in and about London, 1853″ found on victorianlondon.org

The Russian Tsar, Alexander II, was assassinated in March 1881 by social revolutionaries, having survived at least four previous attempts. Known as Alexander the Liberator, he freed the Russian serfs in 1861. His brother the new Tsar, Alexander III, promptly tore up the plans that reformer Alexander II had been about to announce for an elected Parliament. The Tsars continued to rule until the Russian Revolution in 1917.